Judge Young’s 35 year old Decision is front and center again

This Wednesday, September 6th, marks the 35th anniversary of Judge Francis Young’s historic ruling In the Matter of Marijuana Rescheduling. In 1988, after two years of study that included 13 days of public hearings around the country and 18 bound notebooks of testimony (Miami Herald, Sept. 21, 1988), DEA’s Chief Administrative Law Judge ruled that marijuana was improperly classified in Schedule I and should be rescheduled to Schedule II. Given the recent recommendation from DHHS to re-schedule cannabis to Schedule III, it seems a particularly good moment to look back on Judge Young’s timeless ruling.

Want to know more?

Beginning In 1988, Robert and I started publishing the Marijuana, Medicine and The Law series which eventually had five separate books all based on the hearings before Judge Young. Long out-of-print, these books are still available at Internet Archive. The first two volumes contain the testimony, briefs and decision from Judge Young’s hearings. Volume I contains the direct testimony (in affidavit form) of witnesses, pro and con, submitted in the case. Volume II has the legal briefs, oral arguments and Judge Young’s complete decision.

The mechanics of how the hearings happened is a story in itself. It dates back to a 1972 petition to reschedule cannabis, based on medical use, that was filed by NORML and the American Public Health Association. To say the petition languished is a mild description of the events. Lewis Grossman, in his excellent book Choose Your Medicine, calls the progress of the petition “tortuous”.

In the beginning, the DEA (still the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs at this point) essentially just said no and refused to act any further. NORML appealed and the Court told DEA to do better. So DEA sat on the petition even longer and wrote several pages and said no. NORML appealed again and won. The court patiently explained to DEA that it should seek scientific counsel, not its own. DEA sought scientific counsel and still rejected the petition. You get the drift.

Things changed a bit in the mid-1980s. Dronabinol, the synthetic delta-9 THC known commercially as Marinol, had been released to the public via the National Cancer Institute’s Group C program which allowed promising new cancer drugs to be released to the patient population before all the final administrative details had been completed. The medical cannabis movement, which started in 1976, had gained tremendous momentum and there was growing pressure on the federal government to “do something” about legal access. By 1981, thirty-four states had enacted laws calling for intra-state research studies using federal supplies of cannabis. But the feds did not have enough supply for all these states and there was no desire to increase production. So it played a shell game. It promised the public a “pot pill” and released dronabinol which they promised was just like cannabis. Uh huh.

The federal government shell game

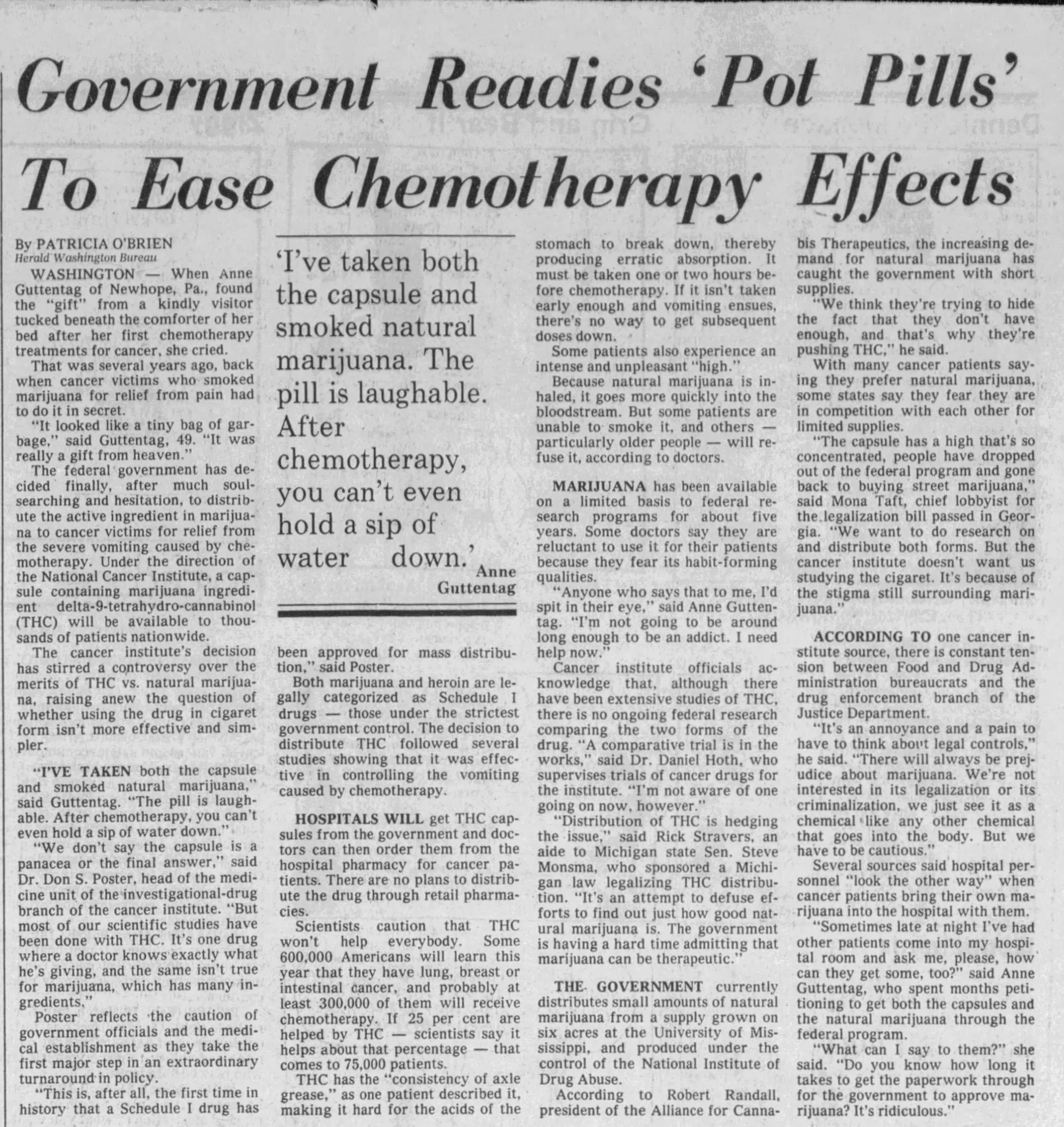

This news clip from the Miami Herald (Nov 27, 1980) is typical of the headlines from the time. Cancer chemotherapy patients were bringing enormous pressure on the FDA and DEA to release federal supplies of cannabis. Instead the feds released dronabinol, a synthetic delta-9 THC.

But in order for dronabinol to get final approval it had to be taken out of Schedule I. So in 1985, DEA approached NORML and the Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics (which had joined the petition) to make a deal: DEA reschedules dronabinol, NORML and ACT don’t object, and DEA will hold hearings on the still-languishing petition before the agency’s chief administrative law judge.

That led to Judge Young’s historic hearings and ruling on September 6, 1988. The Alliance became the lead party in the hearings. With its support from the law firm of Steptoe & Johnson, the Alliance brought tremendous resources to the procedure which included hearings not only in Washington but also in New Orleans and San Francisco.

Judge Young’s ruling was a tremendous victory for medical cannabis reformers but what followed that ruling needs to be a lesson to us all. Especially now.

It wasn’t a total surprise when the DEA, on December 29, 1989, completely rejected the findings of its own administrative law judge. The level of vitriol in the rejection, however, was surprising. The rejection was filled with condemnation of groups like the Alliance and NORML and even a bit towards Judge Young.

Of course, we appealed and won. Once again the DEA was told to get advice from others. It did, with the same result. We appealed again…and lost. It was crushing, but it was also a lesson. We had won the fight with a knockout punch but then we we lost on a technicality.

In that final court battle, we learned the DEA administrator has the ultimate power with respect to scheduling drugs. The administrator can solicit opinions but doesn’t have to listen to them. The administrator can overrule decisions from virtually everyone, scientists and healthcare providers included. In terms of regulations, the DEA administrator has the final say.

So, can or will DEA reject the recommendation from DHHS this time? This is the first time the health agency has aggressively forwarded a recommendation of rescheduling, so this is new territory.

I did some quick research on the web and found a helpful publication from the Congressional Research Service prepared in 2012. It states “The medical and scientific evaluations are binding on the DEA with respect to such matters and form a part of the scheduling decision.” (Emphasis mine.) But DEA has its own five-point criteria for scheduling drugs and could craft a rejection of the DHHS suggestions based on its own findings. Review those criteria quickly and you will see that there is a lot of wiggle room.

So, we are at at critical moment in the long, tortuous journey to reschedule cannabis. There are obvious differences this time around. This time, it was the President of the United States requesting the review. At the time of his request, Biden correctly noted the current situation “makes no sense,” but it has never made sense, and that was never the point for DEA. In this current situation, we are about to find out if DEA has finally managed to shed the shackles of Harry Anslinger who would never accept scientific findings and who practiced the authoritarian dictate of telling a lie continuously so that it becomes the truth.

Oh, to be a fly on the wall in DEA headquarters. The 11th administrator of DEA, Anne Milgram, has a real opportunity to not only remove cannabis from its ridiculous classification in Schedule I. She can also set a new course for the current progeny of Anslinger’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics. There are plenty of drug problems in this nation that deserve the attention of an agency like the DEA, but it must adopt a guiding principle of more science, less fiction.

Administrator Milgram, please bring truth to the table. It would be so refreshing. ❧

*******************

Learn more about the early days of the medical cannabis movement in my new ePub book Marijuana Rx: The Early Years (1976-1996): The Story of the American Medical Marijuana Movement. It is available on this website or at your favorite ePub provider. The cost is $9.99. The book is packed with links to news articles, legal documents and videos. Enrich your canna-library today.